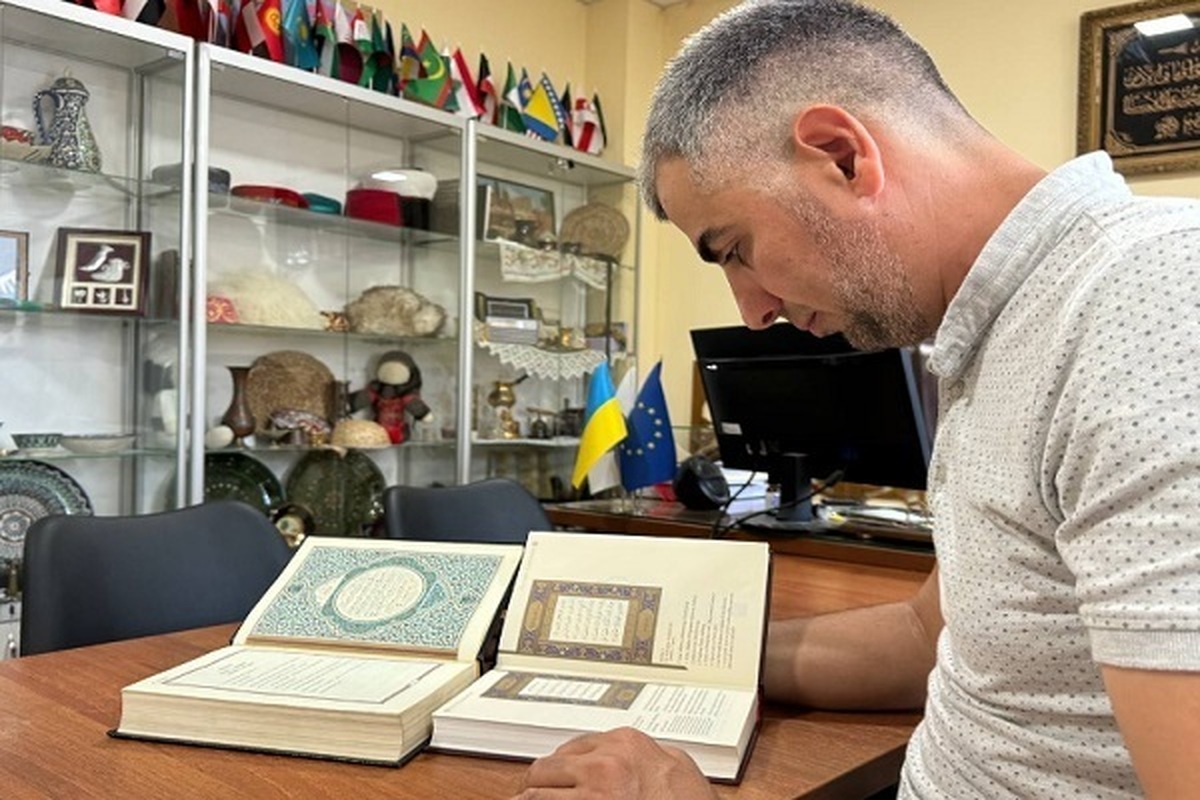

A Look at History of Bosnian Quran Translations

This is according to an article published by the Al-Muslimun Hawl al-Alam website about Bosnian renderings of Islam’s Holy Book, excerpts of which are as follows:

Bosnian is among southern Slavic languages that has become more enriched than Croatian and Serbian because of its cultural interactions with Ottoman Turkish.

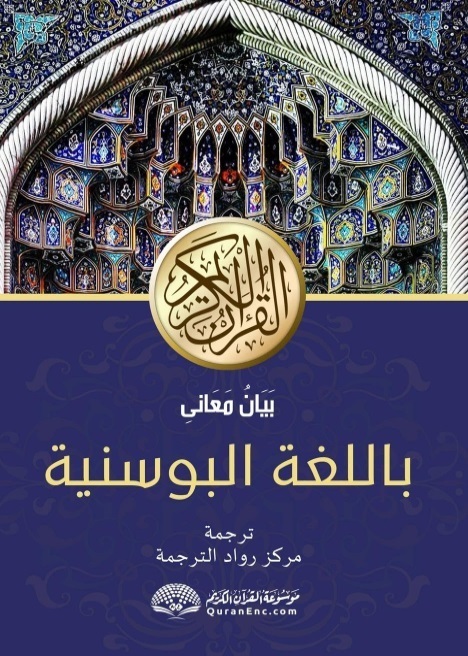

There have been numerous translations of the Quran into Bosnian, all of which have in common the effort to convey the concepts and meanings correctly.

A look at the early renderings shows that the main focus was on meaning, but as time went on, translators paid more attention to discovering the literary and structural values of the text as well.

The first Bosnian translation of Islam’s Holy Book was done by a non-Muslim, the Orthodox priest Mihajlo Mićo Ljubibratić.

It was first published in 479 pages in 1895, after the death of Ljubibratić, and then reprinted in 1990.

With this translation, he wanted to bring Muslims and Christian Serbs closer together and promote dialogue and mutual understanding between them.

He relied on a number of French and Russian translations of the Quran in his rendering, which includes many errors.

The next rendering was done by two Muslim scholars named Jamaleddin Jashvic (1870-1932) and Al-Hafiz Mohamed Banja (died 1962). It was welcomed by the Bosnian people and scholars when it was published in 1937.

The two relied on Persian, Turkish and Tatar translations in their rendering, which was not free from errors either. Their translation was reprinted several times.

Another translation also published in 1937 was by the Mufti of Herzegovina Haj Ali Ridha Qarabac (died 1944). It was a weak rendering containing many errors.

Read More:

During the time Bosnia was part of Yugoslavia, the officials refused to recognize the Bosnian language and did not allow its use between 1945 and 1990.

In this period, only one translation of the Quran into this language was one by Prof. Besim Korkut (1904-1975), who was a graduate of Egypt’s Al-Azhar University.

He benefited from the Al-Kashshaf Quran Exegesis be Zamkhshari in his translation.

Published in 1977, after Korkut’s death, the rendering has been praised for being close to the meaning of the verses.

There were more Quran translations published in Bosnia after the country’s independence from Yugoslavia in 1990.

One was by Mustafa Mlivo (born 1955), which was published in 1994 and reprinted a year later in 719 pages.

Another translation by Enes Karić (born 1995) was published in 1995 and is considered among good renderings of the Holy Book in Bosnian.

But the most successful translation of the Quran in the language is the one by Esad Duraković (born 1948), the head of the Orientalism Department of the University of Sarajevo and a member of the Arabic Academy in Damascus.

Read More:

Titled “Kuran s prijevodom”, it is considered by experts as the best Quran translation in Bosnian.

Duraković is a leading Bosnian scholar of Arabic and Islamic Studies. After graduating from the University of Belgrade in then Yugoslavia (now Serbia) in 1972, Duraković embarked on his academic career in Belgrad and Priština (nowadays Kosovo), with a doctoral dissertation on Arabic literature. Since 1991 Duraković has been affiliated with various academic institutions in Sarajevo.

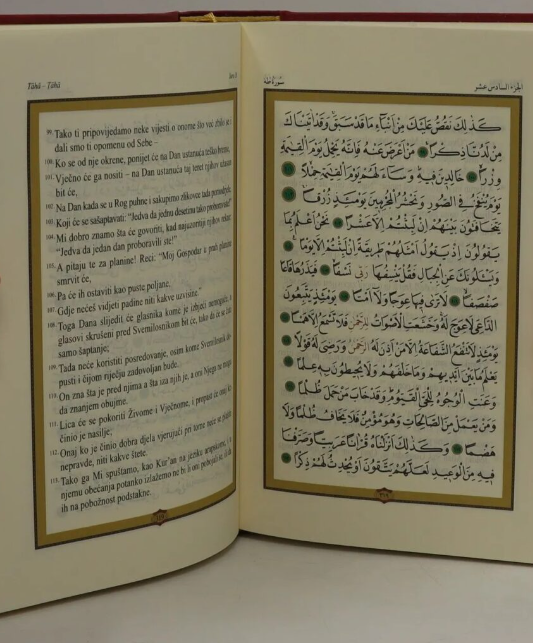

Completed in 2002, and first published in 2004, his rendering is one of the most recent translations of the meanings of the Quran into Bosnian. In contrast to earlier Bosnian Quran translations, Duraković claims to reproduce the actual rhetoric of the Quran; for example, he deems it necessary to follow the rhetorical twists (al-iltifāt) of the original Arabic source text while translating. In one study, in which he explains his translation methodology when working with the Quranic text, Duraković writes that ‘[any instance of] Quranic iltifāt, besides having improved stylistic functionality, is fraught with meaning: it carries the essence in itself of the Quranic message’. In a relevant introduction to his translation Duraković reveals his belief in the need for a translation of the meanings of the Quran that will prioritize the eloquence of the original text rather than simply engaging with theological issues ‘as have other translators previously’.

The artistic tools Duraković uses in order to realize this approach seem to be quite innovative in terms of Bosnian Quran translations. First of all, Duraković undertakes a poetic translation of the Meccan Surahs which paraphrases the meaning in order to conform to a specific rhyme scheme. Surah al-Ṭīn (95), for instance, is rendered with the end-rhyme -e to repeat the -īn end-rhyme found in the original Arabic. Other Meccan Surahs, depending on the style of the original, are also translated using a rhyme scheme. In contrast, his rendition of the Medinan Surahs, due to their stylistic features, are in more prosaic wording (although some verse endings are also given a rhyme scheme), and generally corresponds to the ideals of dynamic equivalence translation theory. A particular strong point of this translation is the absence of literalisms and Duraković’s quite intelligent domestication of key concepts. The style of the translation makes it accessible to a wide audience in Bosnia and the neighboring Balkan states.

There have also been a number of Quran translations in Bosnian, some written in Arabic script and some in Latin, which were never published.

4244594